By Jennifer Griffiths

Our son Jules spent the first 3 years of his life at sea. This is an insight into life on the high seas with a toddler onboard.

It’s exhilarating to be wind driven again, with our sailing boat, Blue Shadow, nuzzling her way through the waves, spray shooting up her flanks. We are galloping along at 7 knots even though we’ve opted for the baby lose-footed mainsail. This means we can tie the boom amidship to prevent it swinging about dangerously. It also means we can leave the cockpit shade cloth up permanently to protect us all from the harsh equatorial sun.

Suddenly we have a metre long sailfish on our line. It leaps into the air and crashes into the sea, snapping the line. Then it leaps once more and is off, swimming free. I’m elated. I feel a strong affinity to this fish. This short episode is a metaphor for what we too have achieved. We too are free again with no attachments to the land slowly shrinking behind us.

Our son was born on Phuket island, Thailand and we spent the first two years of his life island hopping up and down the coasts of Thailand and Malaysia. Two months before his second birthday, we embarked on our first major crossing with him on board – an 11 month journey across the Indian ocean and Equator from South East Asia to South Africa. Our trip took us via Sumatra, Sri Lanka and Madagascar, and through many chains of atolls and smaller islands: Maldives, Chagos, Seychelles, and the Comores.

Many people are awed, or more likely horrified, by the thought of spending a year at sea, cooped up in a small boat with a two year old.

How do you cope? How do you escape? What about the need to play with other children? Haven’t you seen that movie called ‘The Storm’ yet?! They flood us with endless questions, all underscoring their own beliefs and fears about rearing a child at sea.

To be honest, before we sailed away from the security of coastal waters, we too were daunted by what we were about to undertake. One evening shortly before we left Thailand, we sat down to dinner at a small beach restaurant and Peter turned to me in earnest, ‘Do you realise what we are about to do? We could face really bad weather…it could be dangerous…we could need and be far from medical help. Are you prepared to take these risks?’

I remember looking into his eyes. Eyes the colour of deep sea, miles from land. Through all the ocean passages we’d sailed together in both the Pacific and Indian oceans, I had come to trust the man behind these eyes more firmly than land itself. ‘Yes’ I said unwavering. ‘I am. Are you?’ ‘Yes’ he said, smiling. Then we raised our glasses to the months and miles ahead and to the sea horizon in the west. It looked so flat and distant now but soon it would encircle us entirely. A thin disc where the blue of the sea and the blue of the sky rub against each other, with only our boat in the centre, like a pearl.

It took us nearly 2 months to prepare our sailing boat for the open sea. During this time, her 25 year old engine was completely overhauled and we used many island hops up and down the coast between Thailand and Malaysia to find and fix unforeseen gremlins. Once we left there would be no turning back and, as much of our time would be spent far away from any amenities, we needed to bunker food and drink for at least 6 months.

Every nook and cranny of was loaded with pasta, rice, powdered milk and tinned food. The problem was, how to keep all this stuff dry and weevil-free. The tin food was stored in large plastic boxes, so that you could see at a glance what was inside. We resorted to double bagging the rest of the supplies in black plastic bags. Each bag was carefully labelled and the back of our logbook contained list upon list of where things were and how much was left. (We’ve since learnt from other yachts the secret of decanting all dry food, like rice and beans, into large plastic Coke bottles.) Fresh fish would form the staple part of our diet but one can never take its supply for granted.

The week before we left, we bought thick fisherman’s netting to erect a safety net on the guard rails all the way around the deck. Besides aiding Jules’s security, this turned out to be a great saver of balls, toys and everything else left lying on deck. Below deck, we strengthened the large netting in front of Jules’s bunk to protect him in rough sea or, if necessary, keep him in a safe place if both of us were needed above deck in bad weather, for a sail change or other tricky manoeuvre.

This may sound a bit like a prison but it was never perceived as such because we never abused the possibilities. If Jules was awake during a sail change, and the conditions were not too rough, he’d be in the arms of whoever was at the helm.

Once, while at anchor, we’d had a scare, waking up one morning to his cheerful face peering down at us through the hatch above our bunk. We didn’t want him falling overboard while we were asleep so a bedtime story and hugs followed by ‘net up’ soon became routine, even while at anchor in the calmest bay. We started off by only putting it up only once he was asleep so that he didn’t feel locked in, but the net up came to mean ‘sleep time’ and, more often than not, Jules himself would ask for it to go up before settling down to sleep.

Actually, with all these precautions in place, Jules still did manage to fall overboard. Twice!

Once, before he could walk (and before we had the netting up), he literally crawled overboard while we were scrubbing the deck.

He was on an extra long harness for freedom of movement and Peter yanked him back on deck as soon as he hit he water. On the other occasion, he and Peter were fishing. He was standing on a large winch and as the fish on the line swam under the boat, he leaned over the railing too far and toppled into the water. Peter jumped in right behind him and swam him to our dinghy which was trailing behind the boat. Fortunately on both occasions we were at anchor.

Strategies for these sorts of scenarios had to be carefully thought through and agreed upon to prevent tragic misfortune, such as both of us jumping overboard to save Jules while our yacht sailed off into the sunset…. on autopilot!

We decided that if Jules did fall overboard while we were underway, I would be the one to jump after him (unless I was below deck at the time). Peter could then bring the boat around to collect us.

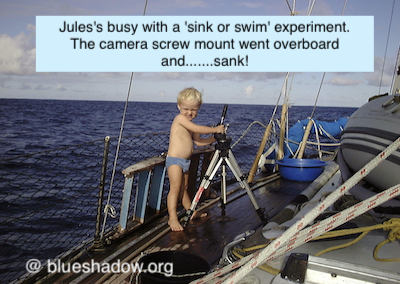

Other sailing couples had warned us about ‘the age of throwing things over board’ and we hoped Jules would be well over this phase before we left coastal waters. This was not the case. We lost numerous articles to his endless ‘sink or swim’ experiments. Buckets, fish lures, Lego, toys, precious shells, the dinghy anchor….are all out there somewhere marking our trail across the Indian ocean. We partially solved the problem by attaching a few waterproof things to the guard rail with long lines so that he could throw them over board and retrieve them again and again. Other more valuable things, like the binoculars, the GPS or cameras had to be kept well out of his chubby little fingers’ reach at all times.

We were fortunate that the sea gods were kind to us while we settled into a routine at sea. Peter and I carved up the night watch between us: two hours each on, two hours off. This forms the pattern of our lives until we reach landfall again. Other sailing couples prefer longer night watches so that each person has at least 3 or 4 hours sleep at a stretch but we have found that 2 hourly shifts work best for us. The average human sleep cycle is one and a half hours and 2 hours gives us 15 minutes on either side of this sleep cycle, to wake up and familiarise ourselves with the conditions outside or to settle down to sleep again.

Activities at sea

When Jules is awake, the person on watch is responsible for him too. Not only for his safety but to play with him, read to him or simply watch over him while he plays on deck. This system works well under fair weather conditions, when Blue Shadow is primarily under autopilot, but when the weather roughens, it simply isn’t possible for the person on watch to be responsible for Jules too. This means that the person who is off duty, and usually in dire need of sleep has to think of ways to keep Jules entertained, usually below deck.

New, stimulating toys are difficult to come by at sea but virtually everything onboard has found a second recreational function. A block and pulley, bucket and line becomes a skilift, a nappy drying on the railing becomes a screen for shadow puppets. Water is a fascinating playmate and we fill large basins so that he can play in them on deck or in the cockpit. We solve the problem of drawing paper blowing away in the cockpit by attaching balloons to strings tied within his reach. Whenever the wind snatches one away, Jules can pull the balloon back to him and grasp it easily to draw on with a felt- tipped pen.

At anchor, we take the canoe or dinghy ashore and look for a new shady sandpit and new playmates. Nature reinvented or village children when there are settlements nearby. And there’s always cause for celebration when other yachts with children onboard are anchored in the same bay.

A collision mat gets turned into a perfect shark free swimming pool.

Deserted beaches provide an endless source of material for impromptu toys. An old plastic sandal or coconut husk becomes a boat with leaf sail, shells become people, a washed-up bouy, stick and bits of vine become a rollerball, clams spades…. We also spend hours observing or interacting with nature, playing in tidal pools, catching fish or hermit crabs, watching insects or molluscs or birds.

One of the blessings of being at sea during these formative years is all the time Jules and Peter have together. Men and women play differently, and offer different learning experiences.

Bad weather ahead

The crossing between Seychelles and Mayotte (French Comores) was our roughest stretch. For 4 days, we had huge seas and wind always forward of abeam gusting up to 45. In the beginning we tried taking Jules outside to play or simply for a bit of fresh air. We attached whistles and other small interesting things to his life jacket and safety harness. At first the huge seas alarmed him but I said, ‘Blue Shadow is dancing. Blue Shadow says ‘Wwweeeeeeeeeeeee’!’

The thought that our boat was enjoying this roller coaster ride seemed to console him and he sat content to watch the waves pile higher. You could see the sky through their translucent toppling bodies just before they washed under us or crashed on deck. Minutes later a huge wave crashed into the cockpit and he was drenched and eager to go back into the cabin again.

Below deck wasn’t entirely dry or quiet either. We were being pounded continuously by huge waves. Their force was awesome and even our ‘usually water tight’ hatches leaked. The windward side kept relatively dry. Fortunately the chart area was on this side, as was Peter’s and my bunk. Jules’ bunk on the lee side was safer (there was little chance of him rolling out) but the hatches overhead dripped onto his bedding continuously. We resorted to hanging spare sheets and towels in front of his bunk to absorb most of the water.

Jules was a star during this stretch of bad weather and we were very fortunate he took the whole thing in his stride. The slightest shift in his attitude could have made our lives a misery. Fortunately this did not happen. We played cars or Lego with him and read or sang or fooled around in a very small part of the saloon downwind of the chart area. Besides his bunk, this was the safest place in the boat for him and fortunately he, like his parents, has a steel stomach. Most people would turn a darker shade of green if they had to sit in that spot under those conditions for more than a few minutes, yet Jules was able to play in this spot for hours without being nauseous.

A few metres away was where we piled our sodden foul weather gear. It became a fun mountain to climb but was often strictly out of bounds for him, being ‘downstream’ of the galley, and the danger of flying pots.

Instant pasta meals kept us going during this period of rough weather. They were tasty and took only 3 or 4 minutes to cook, which was about as long as anyone could survive in the galley without getting injured. Besides fruit and biscuits, raw carrots or tomatoes, this is what we lived on for these 5 days.

When we finally entered the fringe of reef into the broad lagoon surrounding Ile de Mayotte we breathed a deep sigh of relief. There was a lot of whooping and cheering as we motored through the large fleet of yachts anchored near the yacht club off Dzaoudzi, a satellite island inside the fringing reef and headquarters for the French militia and port authorities. We recognised yachts here from all over the world. Cruisers we’d met before in Sri Lanka, Chagos, Thailand or even further afield.

It took us days to dry and repair everything onboard and to catch up with friends. At last we were ready to take the ferry across to the main island to explore this exotic little piece of French territory. For the first time in his little life, Jules had said ‘Julie wants off Blue Shadow’ and we were keen to satisfy this request.

As we step off the ferry, our proximity to the African continent is tangible to all the senses. The jostling crowds, hooting taxis, dusty marketplaces, full of live chickens and bright tropical fruit.

An ebony skinned women, wrapped head to toe in bright sarongs steps off the pavement in front of us, carrying a teapot on her head. Her face is painted with white clay. Her eyes are focused in the distance but her smile is all encompassing, protecting her like a guard rail, from the sea of humanity that surrounds her.

She knows something instinctively, something we too have learnt through sailing with a toddler on board: Attitude is one’s only real environment. Everything else is detail. Or, as the Zen poem puts it: A split hair’s difference/ And heaven and hell are set apart.