by Jennifer Griffiths

August 1998 we spent a few weeks in a remote bay near Exmouth, on the West coast of Australia anchored in a crystal clear waters protected from the open sea by a fringe of coral reef. It was the perfect location for re-corking and sikaflexing Blue Shadow’s decks in calm seas while preparing her for the month long passage north to Asia.

Our intention was to first sail to Cocos Keeling islands, an atoll approximately two weeks north of Exmouth and then, after week’s stay, on to Malaysia before hopping north to Phuket, Thailand.

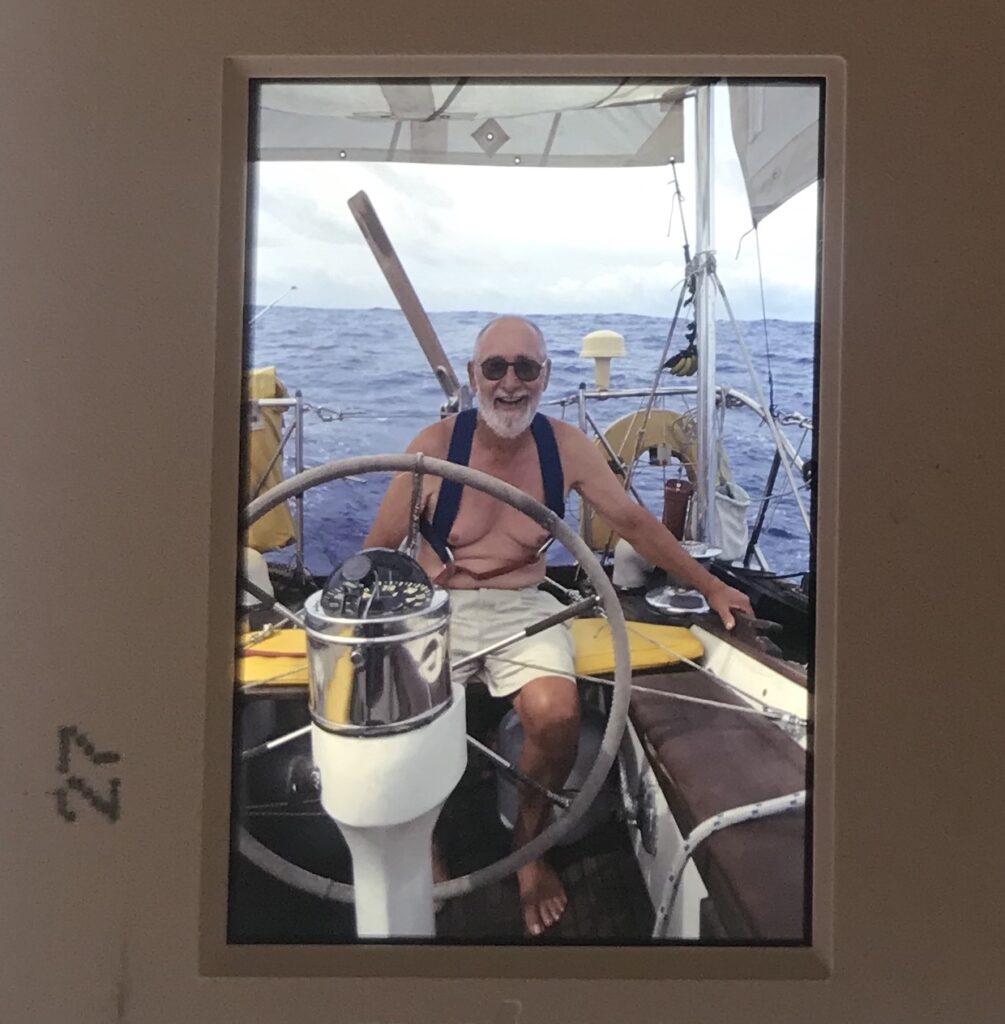

The author, oiling decks at sea.

There were five of us onboard, Peter, myself and a young Swiss couple, Claudia and Daniel, who wanted to log sea miles for their skipper’s tickets, and Christian Dervichian, who was 68 at the time, a competent seaman, dear friend and second father with whom I had sailed on many ocean passages across the Atlantic and also Pacific.

We didn’t know at the time that this very dear gentleman of the sea, renowned for being happiest mid ocean, preferably far from land, making pancakes under the roughest sea conditions to cheer up his crew, was now facing something far deadlier than storms or sleeping whales. Unbeknown to any of us, Christian’s progressively worsening back ache and loss of balance and his ability to hold on in rough sea were due to the onset of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy.

Christian was fond of saying, ”We never abandon the boat, but we have a life raft in case the boat abandons us.” Now his body was slowly abandoning him and, unfortunately, there was no life raft to protect him from the merciless onslaught of this degenerative condition.

Fortunately, while it was still possible, he was where he wanted to be more than anywhere else – at sea and under sail.

Pregnant at sea

Shortly before we departed, I discovered that I was pregnant. I was 41 at the time and had just qualified as a scuba instructor. In Thailand we planned to renovate and refit Blue Shadow for cruising. It was towards the end of August and we already had guests lined up for December and January.

The doctors at the hospital in Exmouth advised me not to make the crossing. They thought we’d be too far away from help should anything go wrong.

After the consultation, a large jolly midwife took me aside and advised me to ask one of the doctors to prescribe a medication that could save my life in an emergency. “If you miscarriage at sea or have an accident and start bleeding heavily this would contract the foetus, making it easier to pass out of your uterus intact.” Thanks to her advice, I decided to risk the passage and sail with caution.

2 September 1998, we left Exmouth in rough seas. Two humpbacked whales broached and tail bragged twenty metres to our port side, waving their tails at us in fond farewell.

While underway, we divided the crew into two teams so that both day and night watches could be shared equally. Each team then had six hours watch during daylight and six hours on at night. This system allows for everyone to get a continuous six hours sleep at night plus another three hours catnapping while on standby for one’s team partner. It’s a flexible system that works well because the individuals within each team can split their six hour watch period between themselves however they wish without upsetting the rest of the crew’s overall routine.

In order to have equal amounts of muscle power and expertise in each team. Peter and Claudia made up one team and Daniel and I the other. Christian agreed to provide backup support, sharing his time with both teams, relieving or accompanying people as he saw fit.

I had been advised by the doctors to try to avoid falling so, unbeknown to Daniel at the time, he would be doing the rougher sail changes during our watch while I took the helm under the auspices of having more experience there.

Back on night watch, I cherish the the solitude of being alone with the ocean and its vast celestial ceiling. Some nights there re more stars in the sea than in the sky and whales blow off like horses, snorting behind us in the dark. After two days at sea, the shaft inside our Aries self-steering wind vane seized and, as there was no way of repairing it at sea, we resigned ourselves to the pleasures of alternating helm duty day and night. Christian’s relief duty became much appreciated, but he tired quickly at the helm and none of us wished to abuse his generosity.

Five days out we ripped our precious no. 2 sail. We needed this sail for the light winds around the equators all hands on deck took turns with needle and thread to make quick work of the vital repair.

Peter and Christian reparing sails

After ten days at sea, we arrived at Cocos atoll at sunrise and joined a fleet of about twenty other sailing boats sheltered in the lee of Direction island just beyond the entrance channel into the atoll

About Cocos Atoll

Cocos is a wonderfully unspoilt atoll necklace of pearls, small sand islands strung together in a large circle of white lace, scantily disguising a dark cleavage of jagged surf-swept reef. The inner lagoon is about ten kilometres across. It is shallow and studded with coral heads, making most of the islands in the atoll completely inaccessible to all but very shallow draught vessels.

Visiting yachts anchor just inside the mouth of the main atoll, alongside Direction inland which is beautiful and completely uninhabited. There are no facilities here whatsoever except a telephone booth and an open aired shack decorated with flags and other memorabilia from passing yachts. Buying supplies or even fetching drinking water means a very wet half hour dinghy trip to a larger neighbouring island and then a ferry trip right across to the other side of the atoll.

Only two of the larger islands are inhabited and there’s a free ferry service between these two islands, situated on either side of the atoll. Home island is populated by a Malay community (approximately 500 people) mostly descendants of families brought here to work on the coconut plantations before the bottom fell out of the copra industry. The other island, West island, is inhabited mostly by Australian government employees and their families (about 80 including children) who run a meteorological/weather station, landing strip, school, hospital, and post office (that’s seldom open), a dilapidated hotel and a few stores. All the buildings are similar government built prefabs with large verandas and corrugated iron roofs.

North Keeling, a separate atoll about 15 miles north of Cocos, is a nature sanctuary and is completely unique. There are no coconut trees on North Keeling and all the original fauna and flora are strictly protected.

Cocos Keeling haș an interesting history. It was privately owned by the Clunies-Ross family until WWI. Cocos islands played a decisive role in the war preventing the loss of many thousands of lives.

On night of 8 Nov 1914 a German warship the SMS Emden, narrowly missed meeting the huge convoy of Allied ships carrying thousands of troops to Europe. Its whereabouts were discovered when it attacked a communications centre on Direction island and a radio alert of Emden’s presence was sent to the convoy. It was then hunted down by one of the convoy’s warship escorts, the HMAS Sydney, engaged in battle and then run aground on one of Cocos Keeling islands. The German crew surrendered and were housed in captivity until they escaped in the island owner’s schooner. After the war, the family business couldn’t survive without their trading vessel and they were forced to sell the island chain to the Australian government.

Coco’s was also used as a refuelling station for Catalina flying boats and as quarantine station for animals en route to Australia. It played a vital role in relay communications during the first landing on the moon and the island’s huge, largely unused runway is still maintained as an emergency landing strip for the American space shuttle.

Providence at sea – an example from Cocos

At sea, it’s often easier to see how everything connects together. How situations we might easily brush off as coincidental fill one with awe.

Here’s an example: one morning while in Cocos, all five of us jumped into our dinghy at the crack of dawn for a very wet half-hour ride to Home island to catch the ferry to the other side of the atoll. The seas were rough in the channel and it took us a lot longer than anticipated. We arrived just as the ferry was leaving and the crew very kindly allowed us to jump onboard directly. They said they’d wait for Peter to tie our dinghy to the jetty, but as soon as he let go, the ferry roared off across the lagoon without him.

We’d seen a sailing boat nearby but hadn’t paid too much attention to it. Now, with so much time on his hands, Peter had a closer look and noticed that it was stuck on a reef and in danger of breaking up.

By the time he motored out to it in our dinghy, the old Norwegian solo sailor had lost his voice and was in a total panic. He’d sailed into the lagoon before sunrise, hadn’t seen all the yachts tucked in the lee of Direction Island right at the entrance to the atoll. Instead he had sailed straight across the lagoon to the jetty, not realising how shallow and studded with coral heads it was and therefore not advised for deep-keeled vessels.

As he himself was stranded, Peter had plenty of time to help the old sailor get his boat off the reef and then help him navigate visually all the way back to where the other boats were anchored. It’s a great help having someone standing forward on the deck, where the coral heads are easier to spot in the clear shallow waters.

The best person to help this stranded sailor ‘just happened’ to be left behind by the ferry at the appropriate moment. Divine providence and prayers answered or just serendipity?

Meeting the atoll’s doctor

At the hospital on Home Island we met the atoll doctor, a large friendly man called Gary Fisher. He made the first scan and blurry picture of what we now affectionately called ‘the honeybear’ because it had already caused me to devour most of our supplies of honey and jam on board. Honeybear was already 3,5cm long, with a strong healthy heartbeat. Dr Fisher put my mind to rest about several issues. He said women have babies everywhere in the world and he himself had helped deliver a few on board boats right here in Cocos. Although I was taking folic acid and other supplements I was concerned about our largely tinned food diet. He said babies were largely parasites and if nutrition were insufficient the baby took what was needed at the mother’s expense. He gave me a phial of Syntometrine in case of emergency and said that even though we had no refrigeration on board and were about to cross the equator, it could be kept in the coolest place on board, against the hull below sea level. Exposure to heat wouldn’t render the medication useless, he said, instead it would make it slightly less effective and in this case one should use slightly more than the package insert recommended. Fortunately I had no falls and the medication wasn’t needed.

Passage to Malaysia

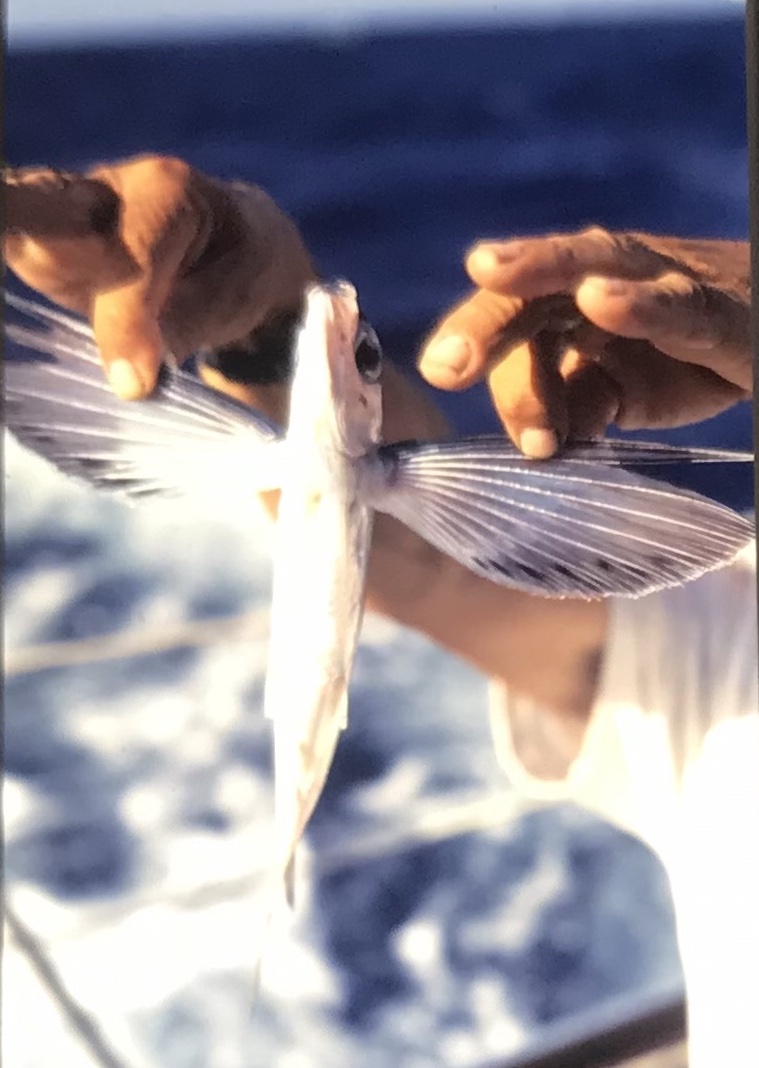

Our passage north across the equator was slow, hot and windless. Only the flying fish skimming the surface broke the monotony of endless motoring across flat seas under a baking sun. We went for a swim mid-ocean, with nothing but six kilometres of deep blue ocean directly below. It’s an eerie sensation, diving down and down, following endless shafts of sunlight into deep blue space then, like astronauts, looking back at the small black capsule above us, our only lifeline to a world more familiar.

Just when we thought we’d need to make an illegal stop in Sumatra to refuel, the winds picked up and we caught a huge golden Dorado. We were back in the wind and in the shipping lanes, cresting Sumatra en route to the Mallaca straits.

That night, huge black clouds chased us, dragging us faster and faster under their big wet bellies. During my watch a squall hit us unexpectedly. With wind direct astern, we were sailing in Butterfly formation with the foresail poled out and for one heart-stopping moment the pole dipped into the sea and I feared it would take us with it.

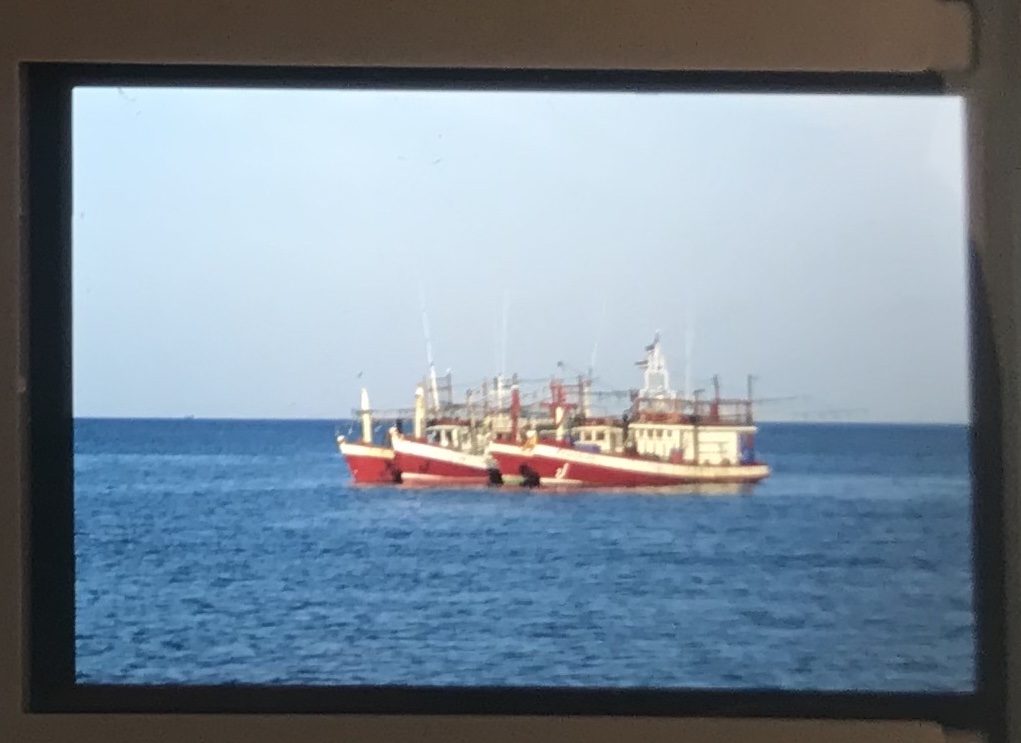

Two days later we sighted land and took shelter behind Butung island on the border between Thailand and Malaysia. Local fishing boats were taking shelter here too, tied up four aside on a rope tackle. We soon found out why they were all tied alongside each other. The spot was protected from the wind but not really suitable for anchorage because the depth gauge couldn’t be persuaded to rise above 30 m even uncomfortably close to shore. Each time we passed by the fishermen signalled us to tie alongside, holding up fresh crabs above their enormous smiles. This was our first taste of Asian hospitality from a culture we have come to both respect and admire.

Next morning, we sailed into the heart of Rebak, a tiny doughnut-shaped satellite island off larger Langkawi Island on the northern border of Malaysia. Rebak is a resort island with a Marina at its centre, where once a mangrove swamp was scooped out and a channel built into the marina, dredged to 3 metres.

Many cruisers develop a love/hate relationship with Rebak because of its uncanny ability to lure boats in and keep them there, sometimes for years at a time. For $10 per day (in 1998) you could hook up to unlimited fresh water and electricity and enjoy all the resort facilities such as gym, swimming pool and games rooms included free of charge, plus 20% discounts at the bar. Protected on all sides by a ring of higher land, temperatures soar inside the marina and the temptation is always there to buy an aircon and become yet another yacht hooked up to life support.

In Rebak we said goodbye to Danial and Claudia, our young Swiss couple. Christian stayed on for another month to watch his beloved boat metamorphose, from spartan 8 single-berthed classic racing boat outfit, with no refrigeration nor upholstery to a relatively comfortable “home” with two spacious semi-private cabins for cruising.

These notes were written in 1998. Some of the facts about Cocos islands and Rebak are possibly out of date.